Landsat has spoiled me. I’ve grown accustomed to seeing historical time series of what a place looks like from above, in this era where we’ve been recording those views for half a century. Of course, I very occasionally find myself wondering how Cahokia in the 11th century would have appeared from space - or Paris before the Haussmann renovations - but when considering access to historical overhead views, I’m usually able to keep a clear line between “BL” (Before Landsat, e.g. pre-1973), and “AL” (Anno Landsatus). But sometimes something is riiiiiight on the line.

I don’t remember when my attention was first grabbed by “The Eye of Quebec” . . .

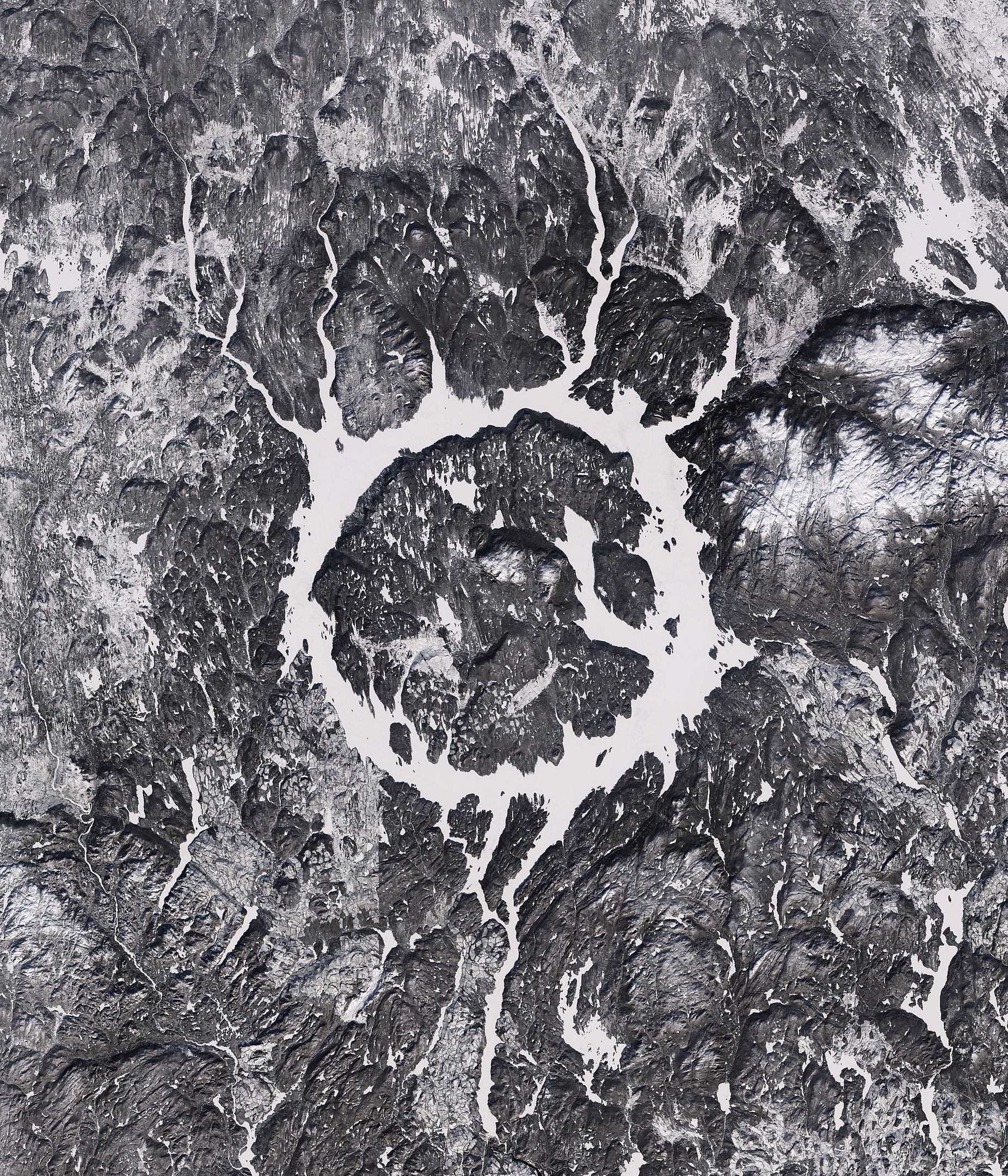

Sentinel 2A winter image of frozen Lake Manicouagan, Quebec, 2017

. . . but I recalled the general details when my wife asked me last week if I’d seen it before: Lake Manicouagan, in an old impact crater from some large chunk of debris crashed to Earth, the void filled in with water, just far enough from the Saint Lawrence that there are no real settlements, though there’s plenty of logging up that way, etc.

I frequently make the mistake of trying to sound authoritative with partial, half-remembered knowledge of a subject. This is no way to go through life, so I went to rectify that situation here, and in the process I encountered information I hadn’t come across before (Canadians, you can skip ahead):

The lake is human-made.

The provincial electrical utility - Hydro-Quebec - began work on the massive Daniel Johnson Dam in 1959, with construction and upstream flooding of the crater completed by 1968. The first Landsat MSS images were collected in 1973. This is tantalizingly close, but unfortunately not close enough; no image of the region captured by Landsat or subsequent instruments does not contain The Eye. But what did this look like from above before it was flooded?

Johnathan Carver’s 1776 map lists it as “Lake Asturagamicook”, drained by the Manicouagan river. It looks very different indeed at this point, though 18th-century cartographers were not known for incredible precision in the American wilderness.

Detail from A new map of the Province of Quebec, according to the Royal Proclamation, of the 7th of October 1763.

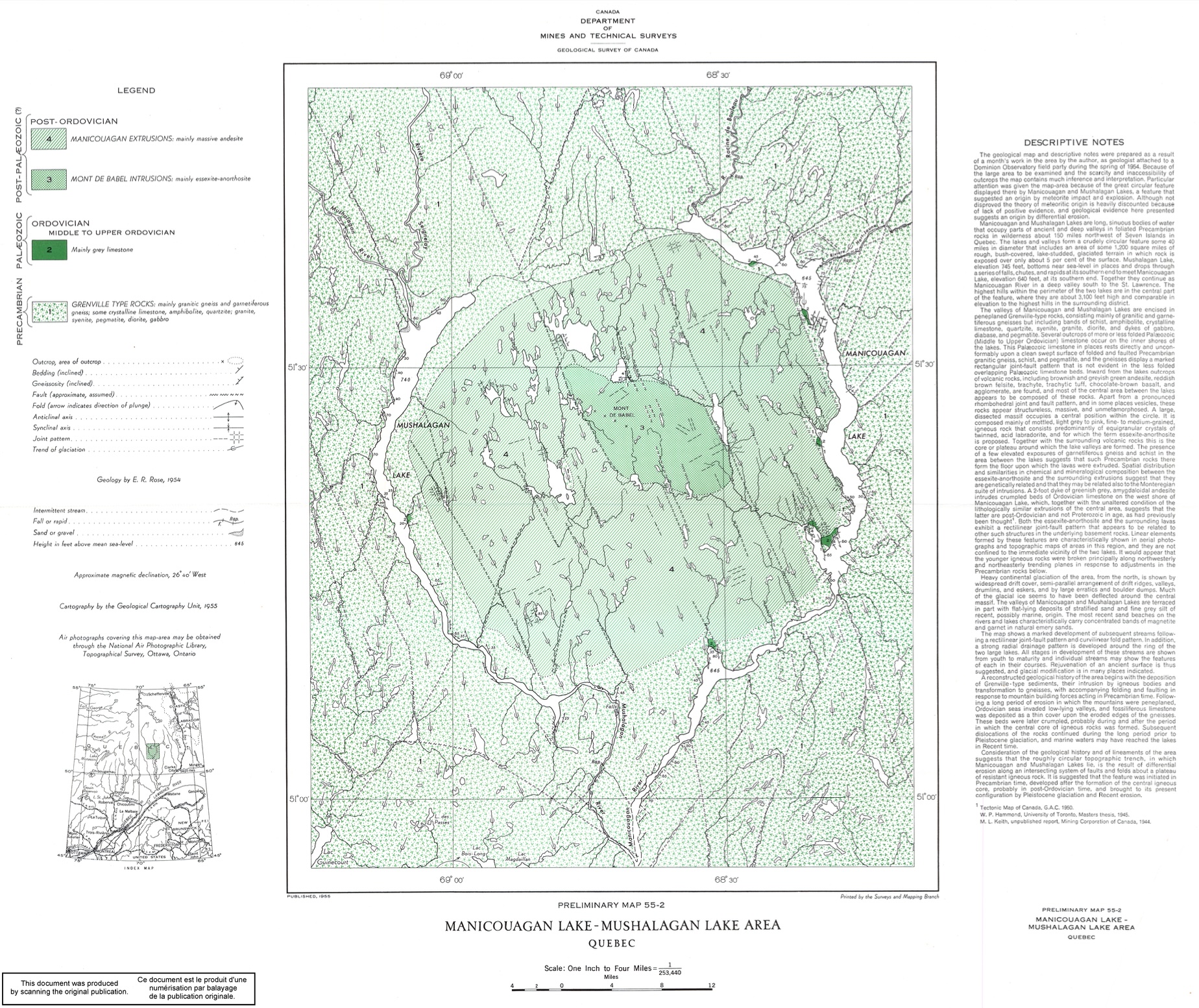

A more recent - and accurate - look is from the 1955 Geological Survey of Canada:

Manicouagan lake - mushalagan lake area, Quebec

The crater structure is very clear in this geologically-focused delineation, with smaller bodies of water occupying the fringes. By 1955, this map was likely informed by aerial photography and photogrammetry, so at least someone had seen this crater from the air before the dam was completed. But what did the crater look like from space? How could I get a satellite view from before 1973?

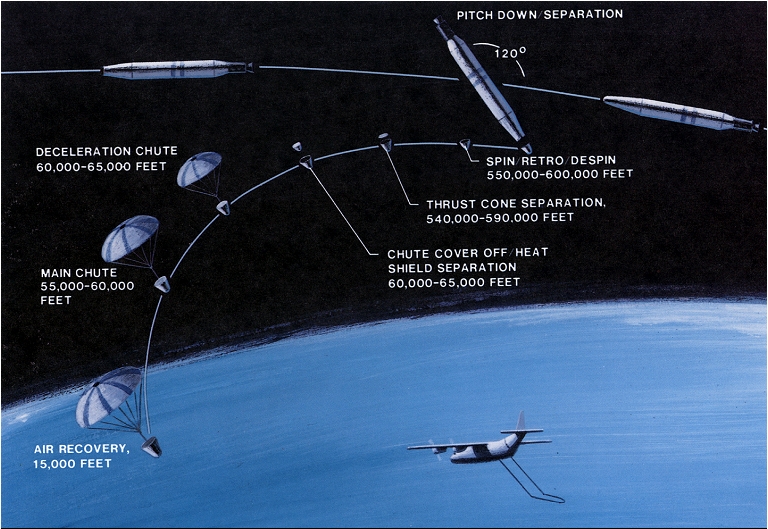

This line of thinking set off memory alarm bells. In a survey I wrote last year covering some of the weird ways we’ve remotely-sensed things, I dug a bit into the CIA’s Corona spy satellite program, which ran from 1959 to 1972, snapping photos of earth on honest-to-god film and sending them back into the atmosphere on parachutes to be snagged by well-timed planes:

Corona film recovery maneuver, NRO

Could there be any Corona imagery of the Eye available to the public (Since the cold war, I’m told, is over)? A quick check of the excellent USGS Earth Explorer library revealed that the 1996 declassification pass included Corona imagery of Quebec from 1965! It’s less than a decade before Landsat began capturing data (digitally - my god, enough with the film canisters on parachutes), and it’s grainy as hell. But for me it was like finding an ancient scroll with forgotten knowledge, the existence of which was only hinted at by subsequent chroniclers:

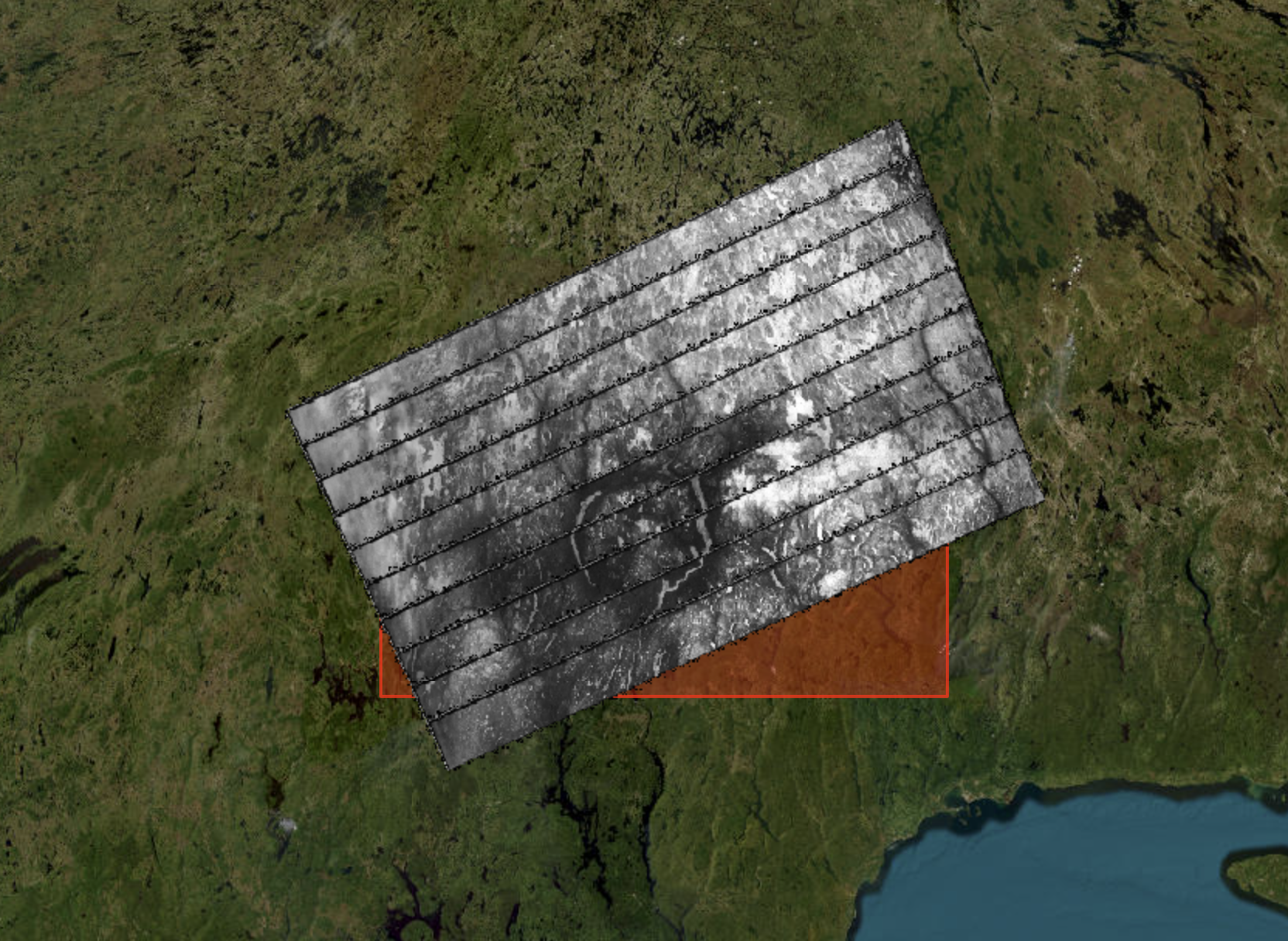

USGS Earth Explorer preview of 1965 Corona imagery over Lake Manicouagan (I haven’t sought better resolution because scans from NARA are pricey)

These winter images show the separated bodies of frozen water and the hints of a round shape, but the Eye is not yet complete. This is exactly what I had been looking for, courtesy of a crazy and probably very expensive effort to spy on the Soviets. This also raises more questions: why did the CIA use precious space-film on mostly-uninhabited Canadian wilderness? If they wanted to scout for NORAD base locations, I assume the Canadians would have allowed a U2 flyover.

I’m pleased to learn that I’m not the only civilian making use of these views. ANU archaeologists have found evidence of ancient settlements in Syria with these images, and recent work by the Landscape Archaeology Research Group shows that it’s possible to apply deep learning methods to Corona captures to map ancient irrigation systems around the world, in hard-to-reach places.

The film strips currently sit in canisters at the National Archives and Records Administration, representing hundreds of thousands of images, apparently. They don’t come close to the spatial and spectral resolution of the instruments we’ve had in orbit since 1973, but for some applications they push back the fog of history by more than a decade, covering some of the most consequential years of the 20th century. What other BL secrets do they contain? Maybe visions of Ada Kaleh? I’m off to look . . .