Whose woods these are, I think I know. His trailer’s in the village, though. He will not see me stoppin’ here To smoke a butt and drink some beer.

–Nathan and Jennifer Hartswick, ca. 1998, with apologies to Frost

Where do I belong? Where am I welcome?

On this Sunday morning at the edge of winter - as the last leaves dangle from one tenacious Norway maple, making a mockery of our attempts to rake - these interlocking questions occur to me.

Skiing enters my mind this time of year. I make my preparations. I turn my mind to past experiences. I question - again and again, like skipping vinyl - whether there’s real value to the practice of careening down mountains on highly-engineered planks. If there is spirituality or meaning to it. If I should be spending my precious energy on something more important.

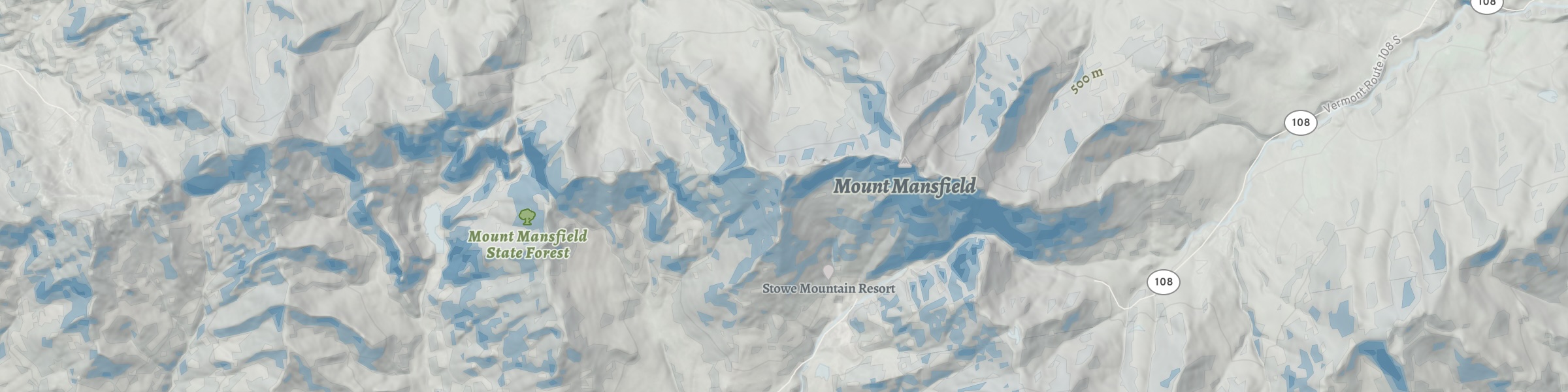

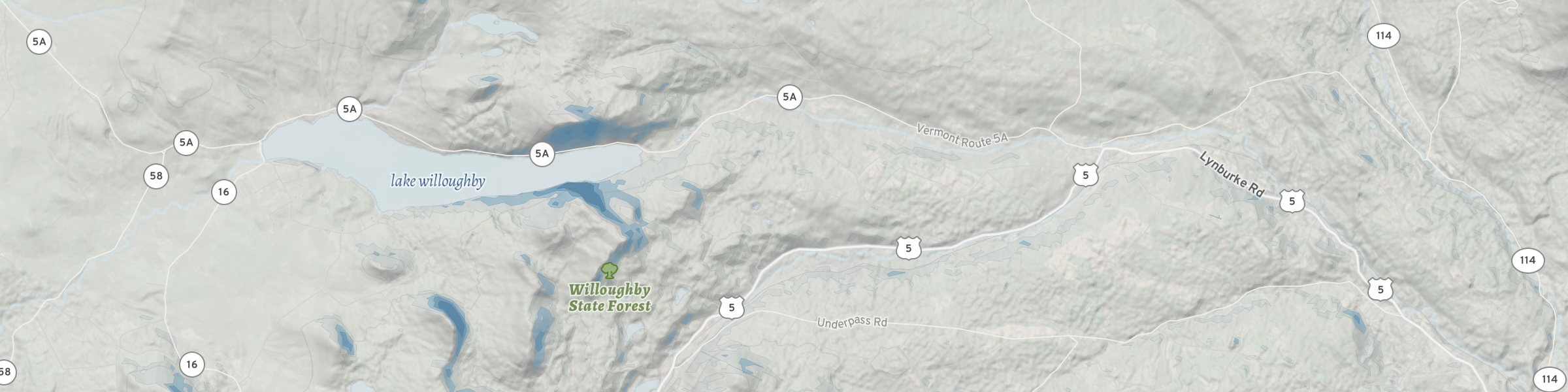

I am close to the ground here in Vermont. I’ve ranged these mountains and forests since before I could walk. I know them better than I do any place else on Earth. To the extent that I could feel like a landscape belongs to me, this is the one I would claim. But it isn’t mine in any real sense.

Paper

Land tenure law dictates that I own a tenth of an acre here in the foothills of the Green Mountains. Ira Allen came through long ago and laid down plots to be sold off to folk from Connecticut and New Hampshire. I’ve now got a title to a slice of a slice of one of those plots, and I’m lucky. But the groundwater doesn’t give a damn about my piece of paper, it just flows through. Same with the winds and the snows.

Blood

In the sense of ancestral and historical connection, this land belongs to the Western Abenaki. This corner of the continent was the last part settled by humans after the ice sheet retreated, making Odanak and Nulhegan relative newcomers, but even they have ten millennia on this land. My ancestors are interlopers and conquerors, come from far away. The fact that they - mostly the much-aggrieved Irish - were themselves conquered doesn’t absolve them or me for helping to visit the same on new places.

Exploits

Historically, the act of exploring was a claim to ownership of land: whoever scales its mountains, levels its forests, plants its fields, and tames its waterways. It’s an old European style of ownership. It’s a surveyor in the Himalayas, it’s a ship bristling with cannons in a river delta, it’s a torch and a herd of cattle. It’s a colonial impulse, and - raised with the associated literature - I have often succumbed to this framing as I scramble to a summit. “This is mine because I climbed it” (never mind the many of my own kind who have been on these peaks before me).

Belonging

My blood doesn’t give me this land. My actions and documents don’t give me this land. Nothing really makes it mine. But perhaps I belong to the land.

This sense of the land having ownership over me rather than the converse is maybe similar to the First Nations approach, but I won’t colonise that idea too. My sense of it is one of a privilege earned, not by conquest, history, or even personal tenure exactly, but by inhabitation. I feel woven into these hills, and can’t imagine that binding lattice anywhere else. So, if I’m lucky, I belong here. I belong in and to the Green Mountains.

Larger questions haunt the edges of this one. I’m in no position to say what it means to belong to the Samarian Hills, or Cap Haitian, or Gujarat, or - and this one hurts - to famine-abandoned villages in Donegal. If I imagine what it would feel like to be moved from this place and to no longer belong to it, I can only begin to sense the pain involved.

Welcoming

The warm greeting, the open door of a new place - welcome brings the world into focus, even when it doesn’t mean belonging. I have been and remain welcome in many places to which I do not belong. I’m welcome with my in-laws in Boston, with mountaineers in Colorado, with colleagues in Valencia. I don’t belong to any of those places, but the people there know me and let me be comfortable in their company. My gratitude for this is incalculable, and I am determined to extend that welcome to those who come to this place.

Snow

There are great conversations to be had in the backcountry skin track here. There are high-fives after big lines, and shared awe at sunrise on steep-growing birches. We skiers seek welcome and belonging in our movements on the land.

Vanessa Chavarriaga Posada speaks about the immigrant experience in the U.S. outdoor community, and more broadly about her relationship with the mountains of her Colombian homeland. She has pioneered ski descents there and around the world, questioning her propriety along the way. Her sense of belonging is complex, and maybe unmoored. She’s a child of the mountains, but which ones, and among which people? Skiing is one of the channels she uses to try to get those answers.

Giray Dadali is a Turkish American skier who has inadvertently addressed my questions head on in his ski journeys to Türkiye. He situates them in the human landscape:

Which has a greater influence; the heritage from which you descended or the culture in which you were raised?

This point rotates a bit in my mind, from influence to belonging, and from a sense of society to a sense of place.

Skiing is one of the ways I express my own belonging, my own weave in these mountains and among the people here. It is an easily-shared activity, full of potential for respect and stewardship. I intimately know the lines and groves of Vermont and I’ve shared them with locals and visitors alike, but truthfully my explorations beyond the Northern Appalachians have been furtive. As I hone in on what it would mean for me to ski beyond my home ranges, I see the contours forming of a welcome without ownership or belonging.

Maybe knowing the difference between seeking and belonging is one of the ways skiing can be meaningful.