Last week I was visiting Ben, a friend of mine, and - as middle-aged men are wont to do - we got onto the subject of collections. While my own accumulative tendencies are focused on backpacks and skis, it emerged that Ben is a collector of vintage posters and magazines. We delved in a bit, and soon stumbled into a corner of his archive that struck elation in my heart: nearly a complete set of the issues of Fortune Magazine from the 1930s and 40s. My mind raced to the first name that would occur to any red-blooded American cartographer in this situation:

Richard Edes Harrison!

Okay, so maybe it’s not totally a household name, but I know that some of you reading this are nodding vigorously.

Richard Edes Harrison was a mapmaking star who flew just sufficiently under the radar that these days his name survives as a Shibboleth. Like Gil Scott-Heron to Kendrick Lamar, or Siméon Chardin to Picasso, Harrison was a progenitor to the mapmakers of today; his influence is incalculable even though very few people know his name.

I’m of the opinion that there has not been enough ink spilled about Harrison’s style and impact1, but I’ll limit my discourse to what I have appreciated about his work. His thematic mapmaking techniques - multivariate choropleths, graduated symbols, cartograms - would be familiar to many students today, but he made them in a time when they were novel, and considerably more technically difficult to achieve. He was also a master of the orthographic view at a time when we could only imagine what the Earth looked like from space. He played with edge-case projections as a way of increasing his readership’s understanding of the world. Through it all he was a consummate artist, imbuing his work with detail and whimsy.

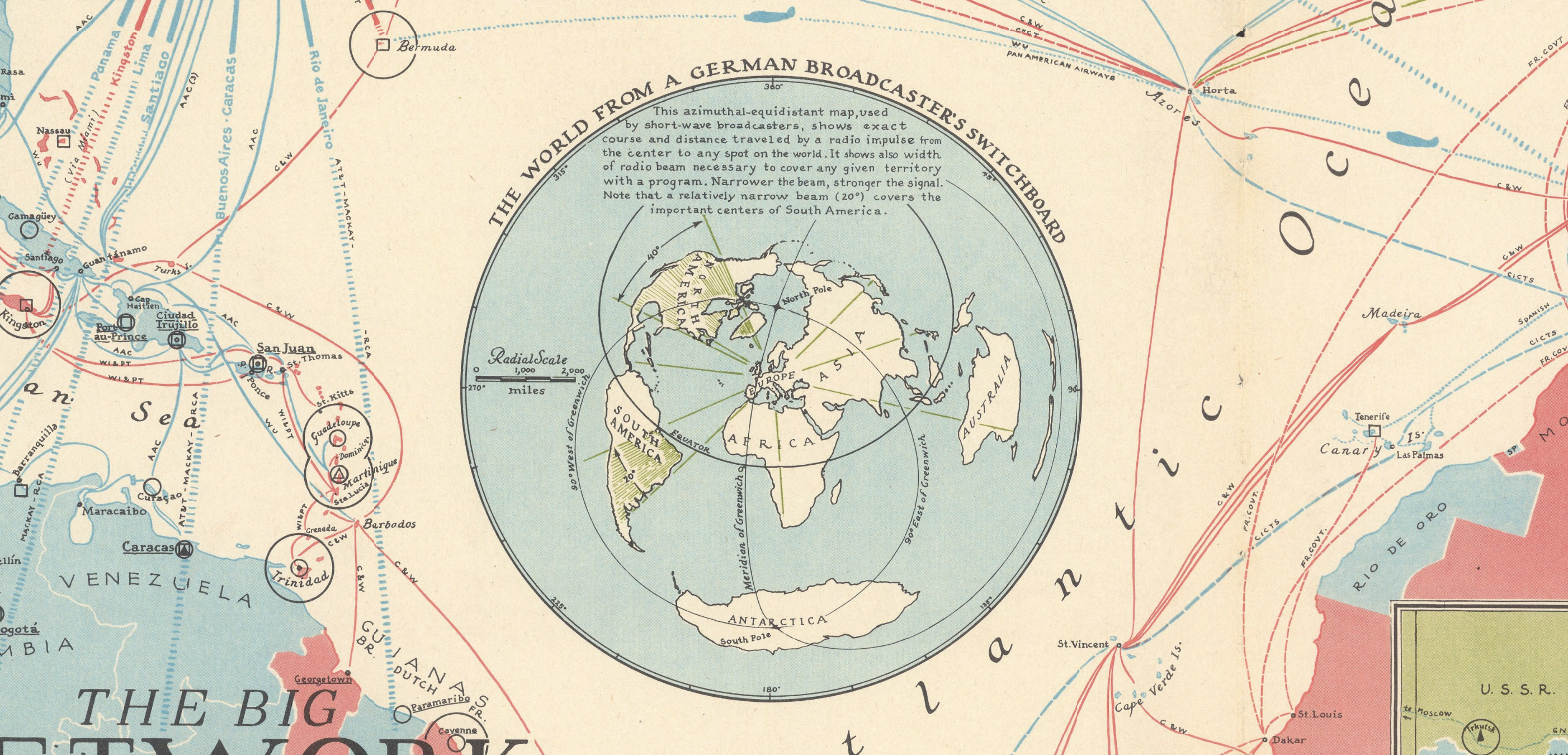

Detail from “The Big Network”, 1939, provided by the David Rumsey Map Collection

Detail from “The Big Network”, 1939, provided by the David Rumsey Map Collection

Harrison was functionally a staff cartographer for Fortune in its heyday, and his work there was - there’s no other way to put this - in the service of capital and power. His maps, viewed by millions of Americans during WWII, were both educational and propagandist. In a sense this was the standard role of a cartograper in the early 20th century, but he approached it with imagination, and today’s mapmakers frequently emulate him, consciously or not.

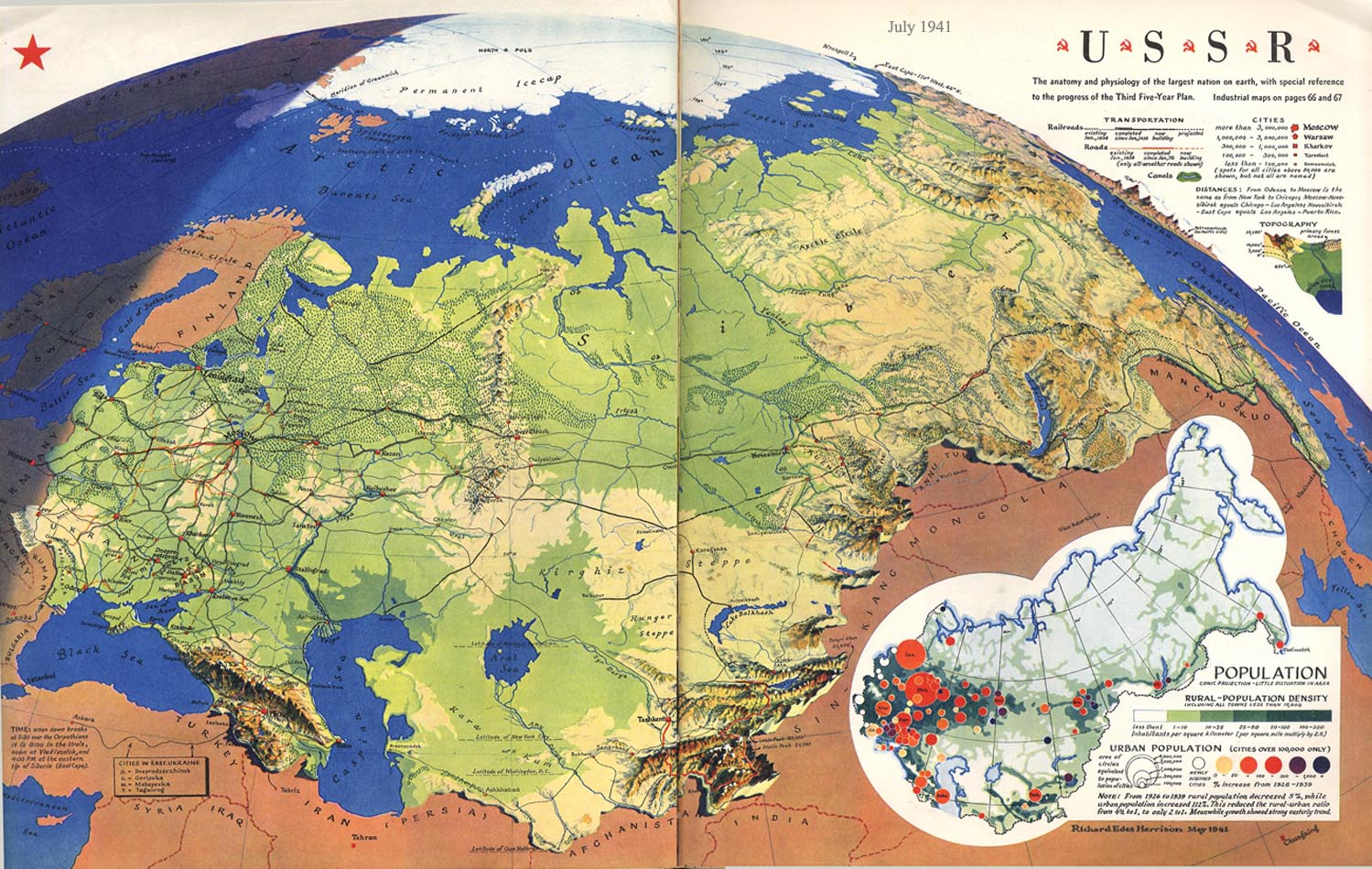

“USSR”, 1941

“USSR”, 1941

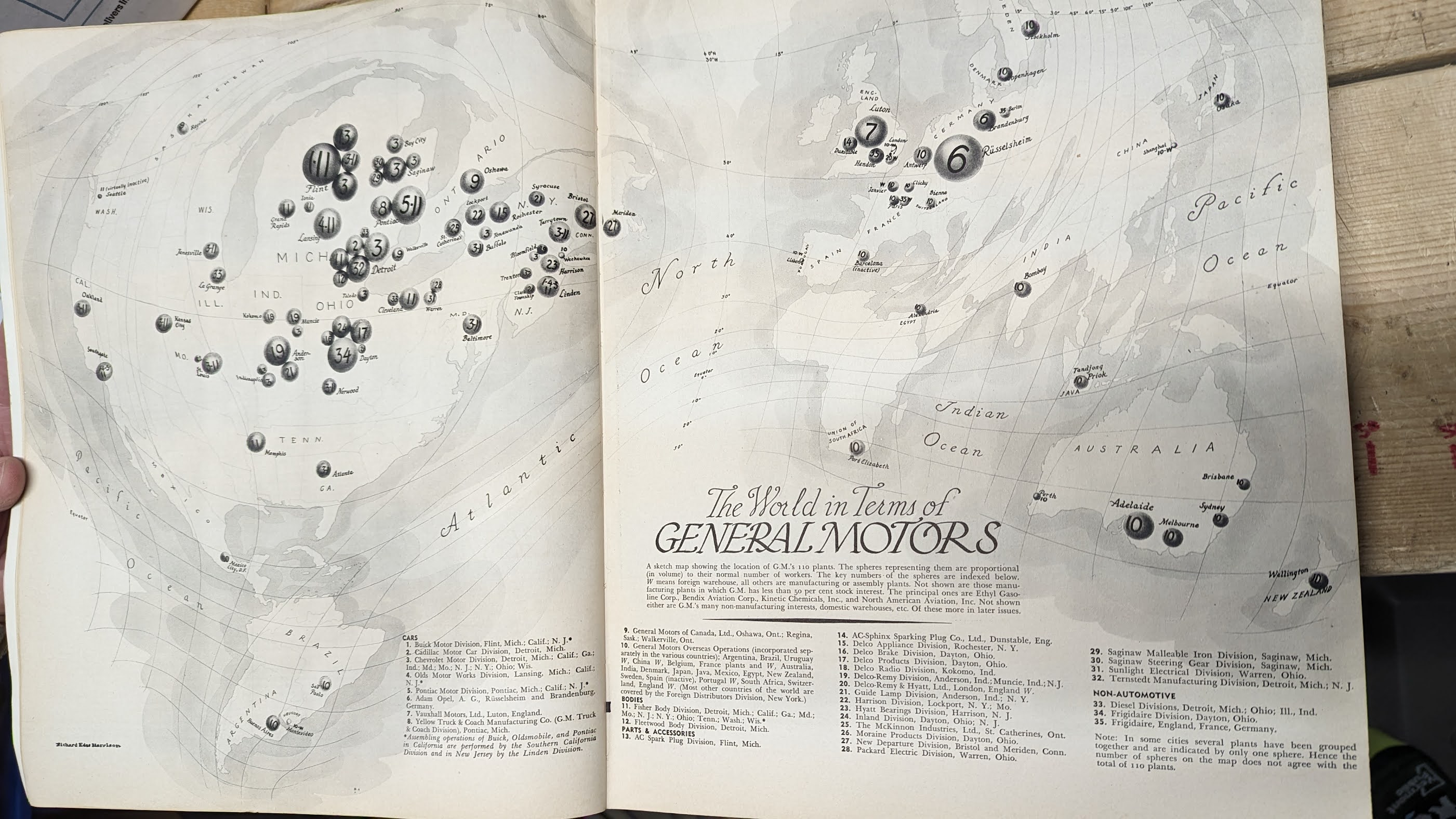

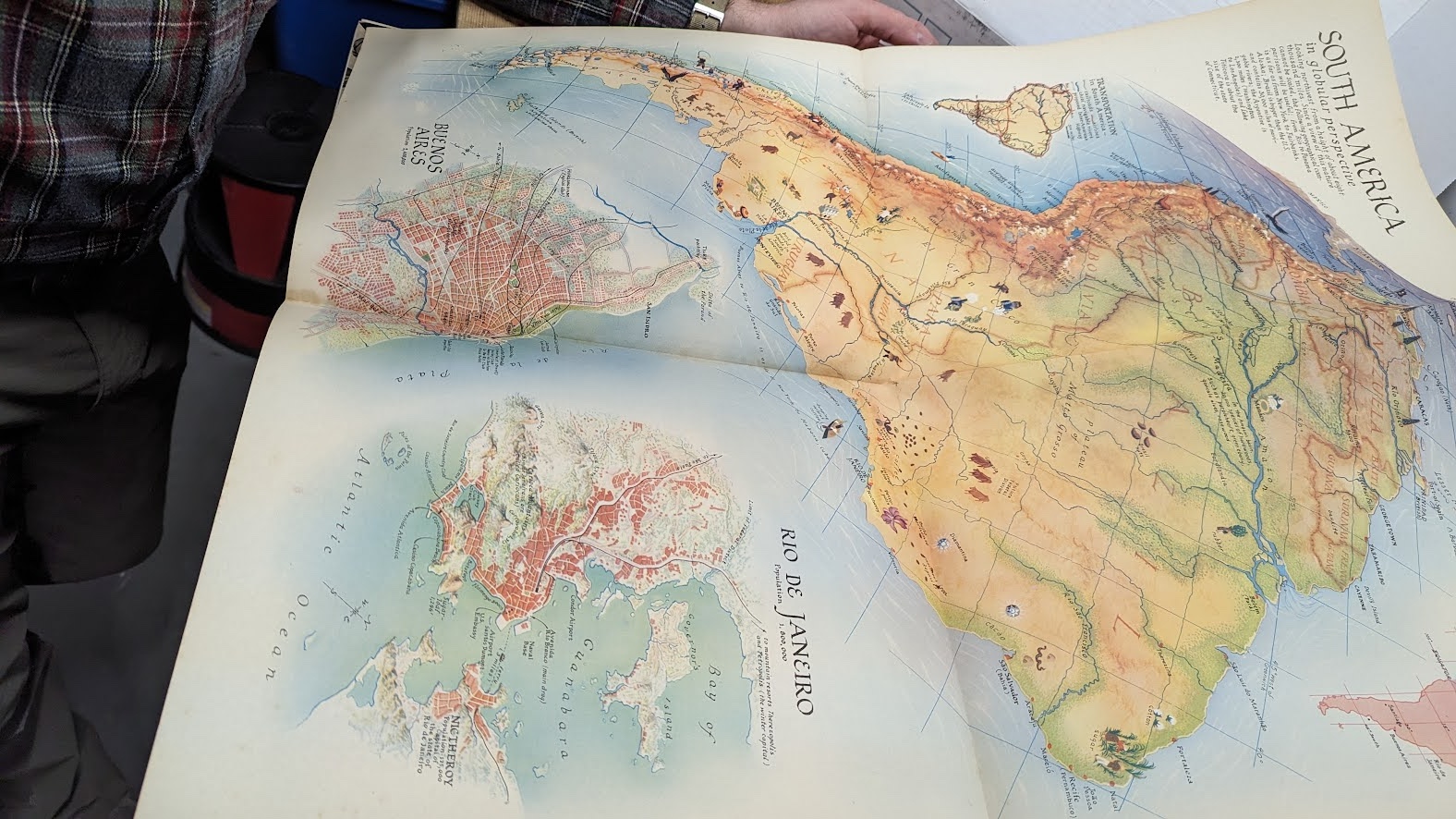

Thus my excitement at discovering Ben’s trove of Fortune issues. As we reverently opened a few of them it became clear that these were books; their heft was down to their 100+ pages, but also the weight of the stock and the very size of the paper. These were meant to be lovingly arranged on coffee tables in the offices and living rooms of the elite. It didn’t take long for us to find some of Harrison’s work: a combination cartogram of GM Corporation’s industrial footprint, and a large fold-out of South America. These were masterpieces.

Handling “The World in Terms of General Motors”, 1935

Handling “The World in Terms of General Motors”, 1935

I think Ben was only a little disappointed to learn that his collection was worth more as spiritual and creative currency to us nerds than as hard cash to the general public. He had originally been attracted to Fortune because of the artistry of the covers in this time period, and it was an additional victory to find such amazing work within.

Ben’s copy of “South America in Globular Perspective”, 1937

Ben’s copy of “South America in Globular Perspective”, 1937

. . . and I was lucky to hold some originals in my own paws, before returning to my daily work of pixels.

-

Right on cue, just after publication of this post, I learned that Dr. Susan Schulten at the University of Denver is working on a full-length book about Harrison’s life and work. ↩