In the Summer of 1934, author Patrick Leigh-Fermor entered the Transylvanian city of Kolozsvár, accompanied by his aristocratic lover and chauffered by their enthusiastic wingman. Even distracted as he was by such great company, he took note of his surroundings:

The old city was full of town-houses and palaces, most of them empty now, with their owners away for the harvest . . . in the great market square, a magnificent equestrian statue showed king Matthias Corvinus in full armour, surrounded by his knights and commanders, while armfuls of crescented and horse-tailed banners were piled as trophies at his feet . . . we had a quick look at the baroque arcades and books and treasures in the splendid Bánffy palace . . . we entered the great Catholic church of St. Michael just as everyone was streaming out from Vespers, and the dusk indoors, lit only by flickering racks of tapers, looked vaster still, and umbrageously splendid . . . an hotel at the end of the main square, called the New York - a great meeting place in the winter season - drew my companions like a magnet.1

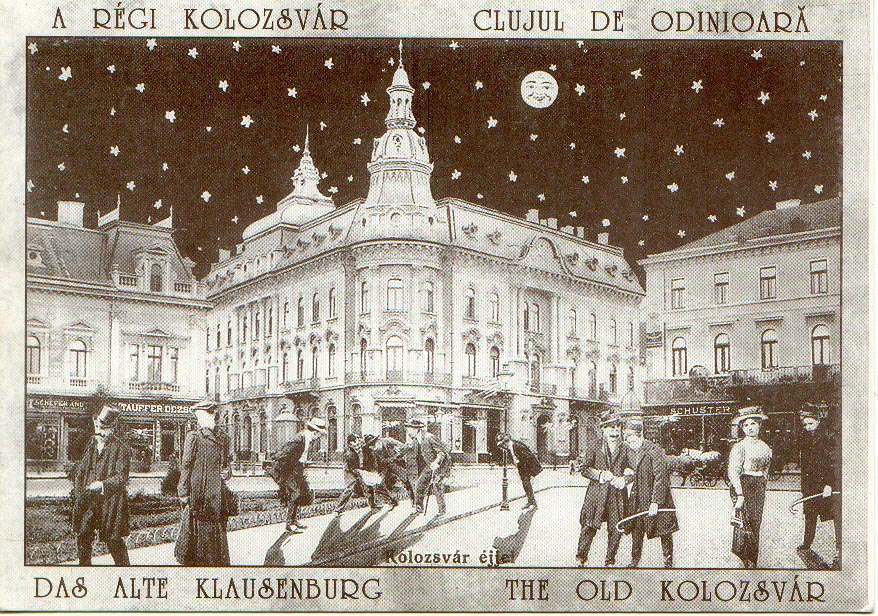

Postcard showing the New York hotel in Cluj-Napoca, late 19th or early 20th century - identified by Tom Sawford and Stefi Timofte (More views of the city here)

Postcard showing the New York hotel in Cluj-Napoca, late 19th or early 20th century - identified by Tom Sawford and Stefi Timofte (More views of the city here)

He moved on from the city after a few glorious days, to continue his fabled foot journey to Constantinople. The cataclysm that was about to envelop Europe would draw a kind of veil on the entire region for decades to come.

In the Spring of 1991, author Dervla Murphy - forced by injury to take the train instead of her own customary walking or cycling - alighted into the same Transylvanian city. She had headed for Romania within weeks of Ceaușescu’s deposition, in the tumult of the USSR’s dissolution, looking for stories from the ground. She was a skilled listener, researcher, and observer - and she noted:

On the summit of Cetatuia Hill I sat on a grassy slope, with my back to the hotel, and gazed over Cluj. To the Dacians and Romans it was Napoca, to the Saxons who founded the modern city Klausenburg, to the Magyars Kolozsvar. In 1974 Ceaușescu decreed that it be known henceforth as Cluj-Napoca, to remind everyone that the Rumanians’ forefathers had been settled here a thousand years before the Magyars’ forefathers moved west from who-knows-where. Frenetic industrialisation has transformed Cluj since 1970 and from Cetatuia Hill its ancient Centru seems a compact oasis of faded beauty, surrounded by mile after monotonous mile of Ceausescu-land.2

Panoramic view of Cluj-Napoca at night from Cetatuia Hill, 2008 - Photo by Christian Adrian

Panoramic view of Cluj-Napoca at night from Cetatuia Hill, 2008 - Photo by Christian Adrian

Leigh-Fermor and Murphy are my bookends for Cluj-Napoca. I have no sense of what happened in those intervening years; only macrohistory, geopolitics, and rumor. For me - one reader in my own obscure corner of the world - a dark age occupies the years between, and imagination takes over.

Sala Colonia

I once stood among Roman ruins along Morocco’s Atlantic coast, and foolishly imagined that I could fill in similar gaps of chronology with emotions and whimsy. At the time, I wrote:

And the colonists were still here when - in 546 A.D. - the news reached them that Rome had been burned to the ground and its people scattered. That the Ostrogoths had ended the empire. Legions had been recalled from Britain, Iberia, Gaul and Syria - pulled back to defend the city - but the inhabitants of Sala Colonia had been overlooked. And they learned after it was done, that they were alone.

Roman ruins, Sala Colonia, Rabat, Morocco

Roman ruins, Sala Colonia, Rabat, Morocco

I wish I could say these were the ramblings of an emo teenager, but alas, this was only ten years ago, when I was in Rabat working for USAID. Beyond my sad grasp of late Roman history (I referenced the wrong sack of Rome! Alaric weeps in his grave! Oh, and those legions were pulled back to fight each other in a vicious series of power grabs.), it was selfish of me to try to buckle a modern post-apocalyptic tone onto stories two thousand years gone. I should have known better.

Exactly what “I should have known better” is a bit tougher to pin down, but let’s try.

Rome never fell

I’m hardly alone in having imagined the [first!] sack of Rome as the start of that blank stretch of Western history known as The Dark Ages. I’m not unique in once assuming it didn’t end until . . . [loosely waves hands] . . . the Rennaisance. In fact, this whole business can be laid at Petrarch’s feet, starting in the 14th century. The concept of a benighted age proved to be a popular one.

In the English-speaking world, centuries of historians held to the narrative that the lights went out once Honorius told the islanders to “Look to their own defense” in 411 CE, and Britannia stood alone. The story holds that those lights would stay extinguished until - depending on who you ask - Alfred commissioned his chronicle, or maybe when William began his well-scribed redistribution of Saxon lands to his fellow Normans, or perhaps when Chaucer got his inspiration for The Wife of Bath. In the interim, only Gildas and Bede yelled out of the blackness, and then only about how dark it all was.

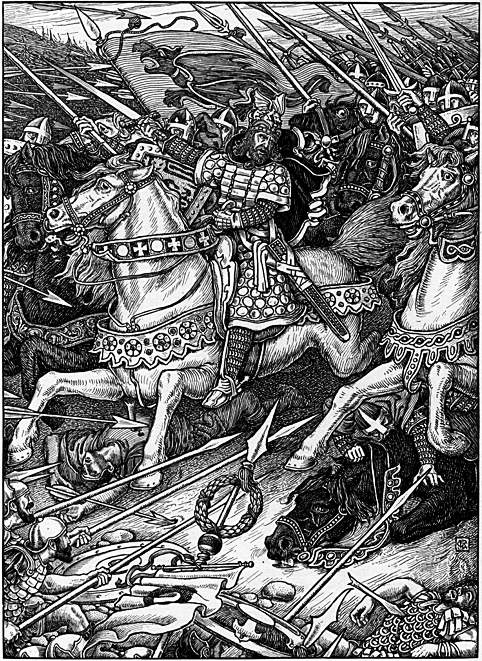

“Arthur Leading the Charge at Mount Badon”, from Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King” - by George Wooliscroft Rhead & Louis Rhead, 1898

This is, of course, baloney. We now know - through a wealth of secondary and archaeological sources - that culture, trade, and population flourished in Britain between the retreat of Rome and the onslaught of the late medieval rulers and their chroniclers, in a rollercoaster of alternating prosperity and decay that would be familiar to us in better-recorded eras. It would have been familiar to other parts of Europe through those centuries as well. Social entropy is perennial, but so is social progress.

In their 2022 book “The Bright Ages” (I’m sure you can see where this is going), Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry are a bit more direct:

The mosaics of the emperors are symbols of a Mediterranean world, a medieval world, always in flux, with permeable borders, and signs of movement and cultural intermixing everywhere you look. And so we look. We also listen to the mixing of languages in the sailors’ patois and to the commonality of multilingualism across Europe, Asia, and North Africa. We find marketplaces where Jews spoke Latin, Christians spoke Greek, and everyone spoke Arabic. We find coconuts, ginger, and parrots coming in on Venetian ships that would eventually reach the ports of medieval England. We mark the brown skin on the faces of North Africans who always lived in Britain, as well as on French Mediterranean peasants telling dirty stories about horny priests, raunchy women, and easily fooled husbands.3

They go on to point out that - quite literally - the Roman empire didn’t actually fall to either group of marauding Goths; it was far too vast, complex, and powerful for one lost battle at one important city to bring it to ruin. Among other inheritors, Byzantium stood for another thousand years - its citizens rightfully calling themselves Romans - before the Crusaders and the Ottomans finally ended the party. And even then . . .

Reproduction of Byzantine Deesis Mosaic, original ca. 1261, located in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul - Metropolitan Museum of Art

Reproduction of Byzantine Deesis Mosaic, original ca. 1261, located in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul - Metropolitan Museum of Art

USSR & SPQR

In the time of the USSR’s dominance in Eastern Europe, language and policy conspired to reduce the flow of information to the outside world, though it was hardly difficult to find the news if you looked. Romania under the Stalinists and the Ceaușescus was sometimes prosperous and sometimes terrorized, and individual stories escaped the regime’s gravity and made it to the West in various forms. I recall listening to a CBC broadcast in the late 80s with testimony by a dissident who’d fled Bucharest and married a Canadian. Radio Free Europe plugged away with its bulletins. Word got out, if you were looking.

In its corner of Romania, the city of Kolozsvár/Cluj-Napoca endured communism, and its people persisted with the broad spectrum of human experience that can be found in any population making its way through history. The dark age of Kolozsvár wasn’t that at all for the citizens living through it. It only exists in my reckoning because the works of two prolific Irish writers4 crossed my reading list, and even then it can be easily banished with some cursory research. Light is cast into the gap by a wealth of local chroniclers - by Herta Müller’s harrowing book “The Hunger Angel”, by the reformed post-realism of Paul Georgescu’s novella “Pilaf”, by the metaphysical essays of Cluj-based Anatol Baconsky, along with his honest-to-god visitors’ guide to the city.

Europe’s medieval period is the same: it’s only ever been empty for those who wished it so and ignored the evidence, perhaps so that it could serve as a metaphor.

Dark purposes

A dark age is not a time of universal calamity, nor is it a time of utopian dreamscapes. It isn’t even a gap in information: the people who live through it have all the stories and statistics, if only you can ask them.

A dark age is a gap in perspective - the perspective of the observer. In the cases of Cluj and Sala, the gap is in my perspective. Or, it was, but it’s since been steadily filled with the not-at-all-hard-to-find scholarship of recent generations. I’ve got no excuse to leave those gaps unfilled, and I’m just some dude who reads and thinks about this stuff.

Standing Lamp With Running Dogs, Byzantine, ca. 400-600CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Standing Lamp With Running Dogs, Byzantine, ca. 400-600CE, Metropolitan Museum of Art

The folks who really have no excuse are the historians - armchair and professional - who persist in maintaining the construct of the unknowable, chaotic medieval period; mercifully their numbers seem to have receded in the 20th and 21st centuries. Also excuseless - and troublingly, more plentiful - are the leaders who invoke the dark ages to draw fear out of their constituents and subjects, who liken Honduran or Syrian refugees to Visigoths, who equate capital-P-progress with the collapse of empire.

As Gabriele and Perry put it:

The myth of the “Dark Ages,” which survives quite ably in popular culture, allows the space for it to be whatever the popular imagination wants. If you can’t see into the darkness, the imagination can run wild, focusing attention on and giving outsized importance to the small things you can see. It can be a space for seemingly clean and useful myths, useful to people with dangerous intentions.

In a way, what I’ve written here has been a long-winded response to a particular group of clowns: Roman Imperial Nostalgists. They pop up regularly in the ranks of white supremacists, among people who think drag queens are scary, and alongside cowardly, orange-hued populists (that there are n > 1 of this type is astounding, and not in a good way). They are always wrong, but that doesn’t make them less dangerous. I’d ask you, dear reader, to carry a message wherever such clowns can be found:

A dark age is just an intellectual choice; there’s always light to be found therein.

I need to keep reminding myself of this as well.

Coda: Birdoswald

Last year, fresh from the pandemic, I found myself standing in gentle rain on an open ridge in Northern England, trying to jumpstart my imagination. At the site called Birdoswald, where some of the last Roman legionaries were left to staff Hadrian’s wall, the fortress ruins are obvious, enduring, and the subject of several centuries of archaeological scholarship. I had wanted to come here since I’d first heard of the place, not long after I left Sala Colonia, because of my continued fascination with the edges and ends of empire.

But Birdoswald felt different. Maybe it was the particular history of the legion posted there - coincidentally, recruited from Dacia, in what is now Romania. Maybe it was the research that had uncovered Roman customs and activities persisting at the site more than a hundred years after the [first!] sack of Rome, as the Saxons secured their hold on Britain. Maybe it was the eventual abandonment of the fortress and its surrounding villages, a rare case of a once-populated place truly becoming uninhabited (but for all the sheep) in the long term. Maybe it was the comprehensively-arrayed interpretive materials at the site, informing me of all of the above.

Whatever it was, my imagination - in search of dark corners of history and geography to colonize - could only find light and knowledge at Birdoswald. I walked away as the rain continued.

A current inhabitant of the ruined fortifications near Banna (Birdoswald) Roman Fort, Cumbria, England

A current inhabitant of the ruined fortifications near Banna (Birdoswald) Roman Fort, Cumbria, England

-

Fermor, Patrick Leigh. 1988. Between the Woods and the Water: On Foot to Constantinople from the Hook of Holland: The Middle Danube to the Iron Gates. Penguin Books. ↩

-

Murphy, Dervla. 1992. Transylvania and beyond. London : Murray. ↩

-

Gabriele, Matthew and David M Perry. 2021. The Bright Ages : A New History of Medieval Europe First ed. New York NY: Harper an imprint of HarperCollins. ↩

-

It is with an appropriate amount of chagrin and irony that I add a recently-uncovered addendum that perhaps Leigh-Fermor never went to Transylvania at all on his trek, and fabricated this part of his story from secondhand sources. Dark age bookend, indeed. ↩