The snow is flying this morning in Vermont - early, it seems - and therefore it’s as good a time as any to reflect on last winter in the Northeastern mountains.

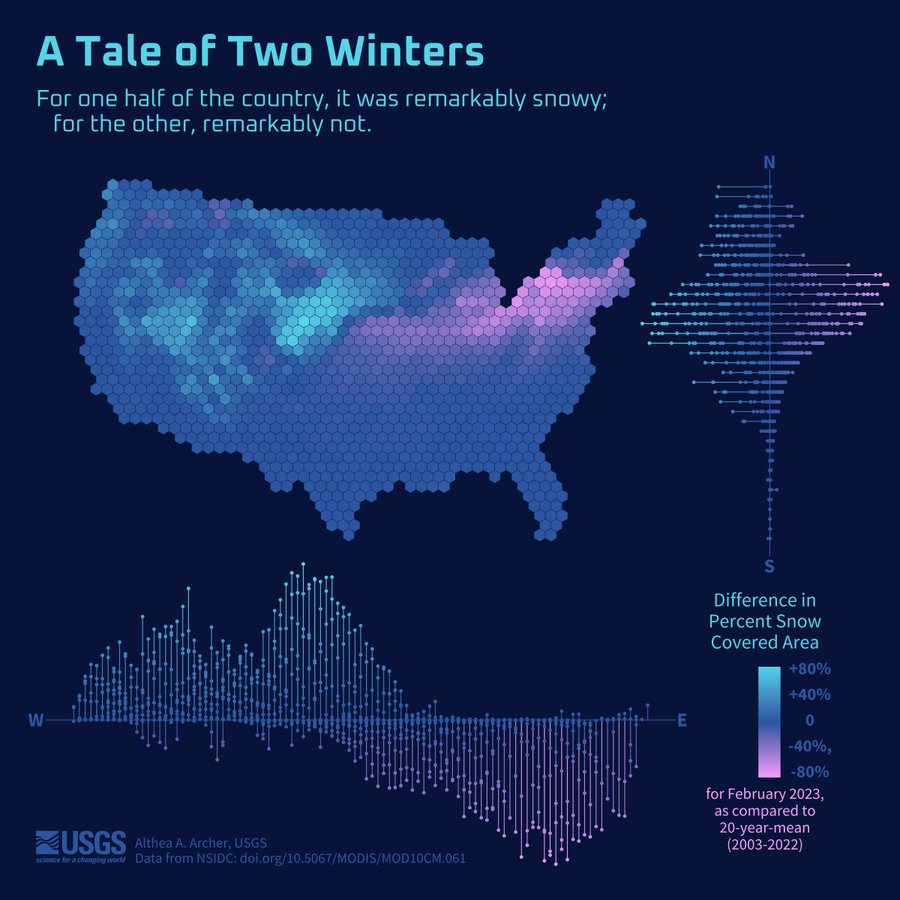

I was sent on this train of thought by the publication of an amazing USGS map of regional snow anomalies in 2023. The picture of East/West divergence is dramatic: it’s clear that the Rocky Mountain West and the Sierras were overloaded with snow. At the same time, the East coast experienced historic lows of snow cover, with the exception of the lakes region around Buffalo, ensconced in its perpetual blizzard.

Map by Dr. Althea A. Archer, who has done a lot of other great dataviz work for USGS.

Map by Dr. Althea A. Archer, who has done a lot of other great dataviz work for USGS.

The thing is, this picture is not familiar to me at first glance. I mean, I lived it; I was in the Northeast all last winter, and I remember it as one of the best ski seasons in decades. The vibes that remain with me from the last snowpack in the Green Mountains are very good - I recall being in the backcountry a ton, finding great lines in great company.

Despite my dabblings and adjacencies in college and grad school, I am really not qualified to say much on matters of the hydrologic cycle, atmospheric dynamics, or El Niño. But I trust the USGS - using spaceborne sensors that I am familiar with - when they say that there was a huge divergence last season, and that the East suffered a snow drought. So why does that not mesh with my own remembered experience?

It doesn’t actually take all that much reflection for me to grasp that there is a substantial difference between a winter and a ski season. My fellow skiers and I constantly conflate the two in our conversations, our planning, our sense of stoke - but there are quite a few characteristics that make one good or bad, but have no impact on the other. Let’s consider the features of my last ski season that were independent of the snow-catastrophe depicted in the map above:

- My kids are old enough to ski with me now - nay, perhaps they shred harder than I do.

- I got out into the backcountry with the regularity of a predawn routine.

- I sought out varied terrain, throughout New England and Quebec.

- More than in years past, I opened up to the idea of hitting the snow with friends, family, acquaintances, whoever was up for it.

Getting after it in the skin track, Cotton Brook basin, Vermont - March 2023

Getting after it in the skin track, Cotton Brook basin, Vermont - March 2023

New vistas and new companions were balanced by familiar slopes and long-established relationships. My good ski season last year was as much a product of social and geological circumstances as it was of the paltry snowpack. And if I think back, I realize it was paltry, but it didn’t matter. There was nothing on the ground until February, so we trained on the made-snow of nearby resorts. We found a half inch of ice on top of 18 inches of powder on the Bolton-Trapp traverse, but all the scraping and crunching ended up being hilarious. A hard January rain in the Chic Chocs left lurking danger on the big lines, so we sought out powder-bathed runnels in the trees. We made it work. Making it work is, in fact, a point of pride for East coast skiers.

Everyone’s favorite buried layer, on Mont Lyall, Quebec - February 2023

Everyone’s favorite buried layer, on Mont Lyall, Quebec - February 2023

But the characteristics of a bad winter are measurable and obvious at macro scale, and the impacts are far greater than a lack of stoke. Even in the Northeast - where a light snowpack doesn’t condemn us to parched crops and burning forests [as much, anyway] - a bad winter brings invasive pests in its wake, it endangers local fauna, and for god’s sake, it messes with the maple syrup harvest!

I’m guilty of letting my good ski season override my memories of a bad winter. It’s a mental fakeout not totally unrelated to that of the climate-skeptic who declares a single blizzard to invalidate a century’s terrifying-but-very-real data. Fortunately, skiers seem more likely than most to recognize the danger, and some have banded together to translate stoke into climate action.

I’ll be keeping an eye on the stats this winter, and trying to take action myself.

The meltout, still skiable on Mount Mansfield, Vermont - May 2023

The meltout, still skiable on Mount Mansfield, Vermont - May 2023