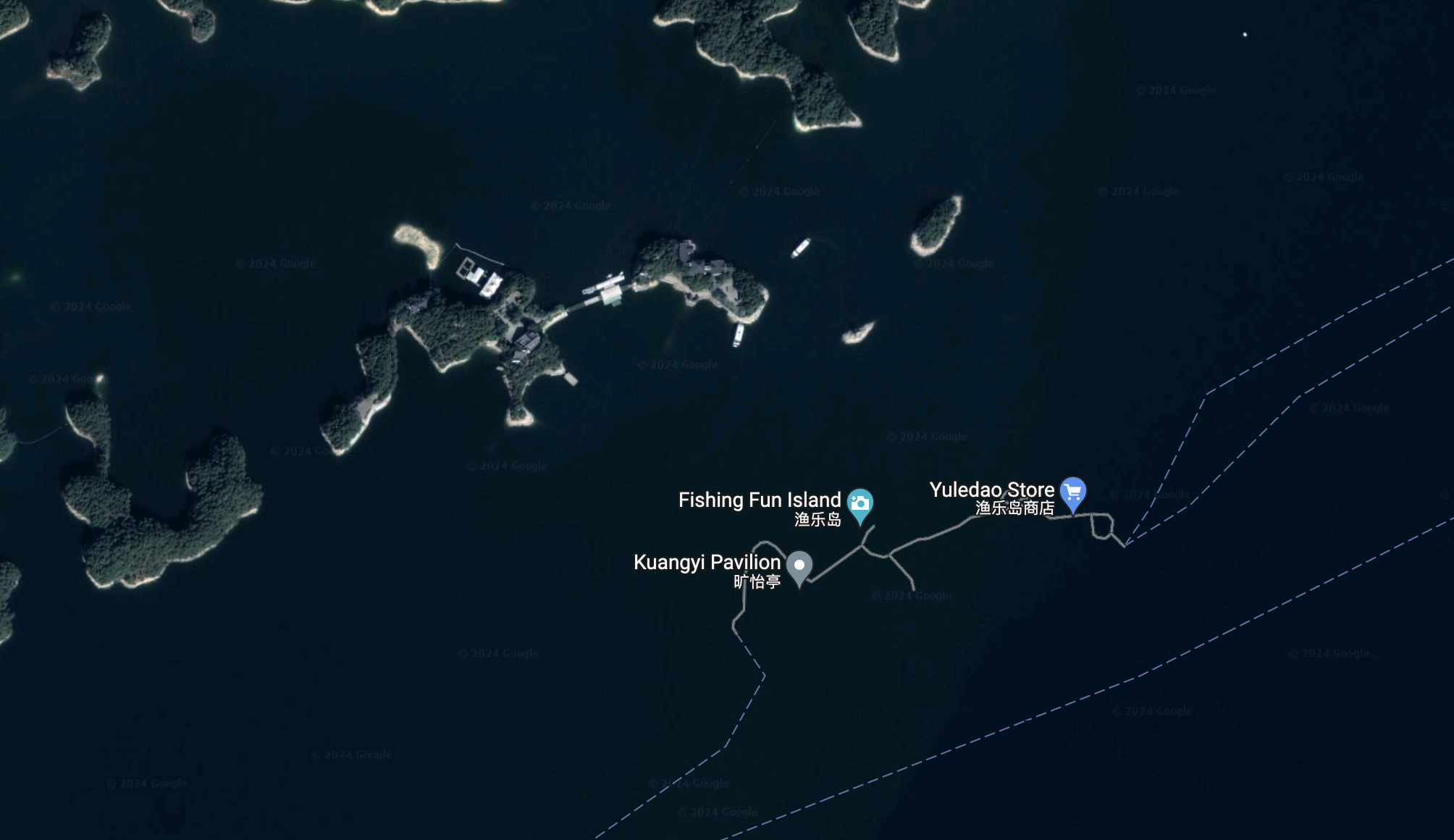

The practical work of digital mapping varies pretty wildly from place to place. I was reminded of this as I stumbled onto a great example of the infamous displacement of imagery and road vectors in Google Maps within Chinese territory:

If you can find it, “Fishing Fun Island” actually sounds kind of awesome.

If you can find it, “Fishing Fun Island” actually sounds kind of awesome.

I’m hardly the first geographer to be both appalled and mesmerized by this policy - very much in keeping with China’s general digital control strategy - but this encounter also turned up new information for me about how it works.

A quick napkin sketch about map projections: Because the world is not actually flat (nor actually spherical, unfortunately), mapmakers rely on mathematical models to transform the world into a two-dimensional representation. And there are thousands of different such models - called datums to represent the shape of the Earth, or projections to represent how that shape is warped onto paper or phone screens - each with a specific application.

My assumption about China’s national security concern was that they required a blanket offset - say, half a kilometer or so - between different base data types and real-world coordinates. I also assumed that it was largely optional; if you mostly don’t offer services in China (like my employer), you can ignore the offset.

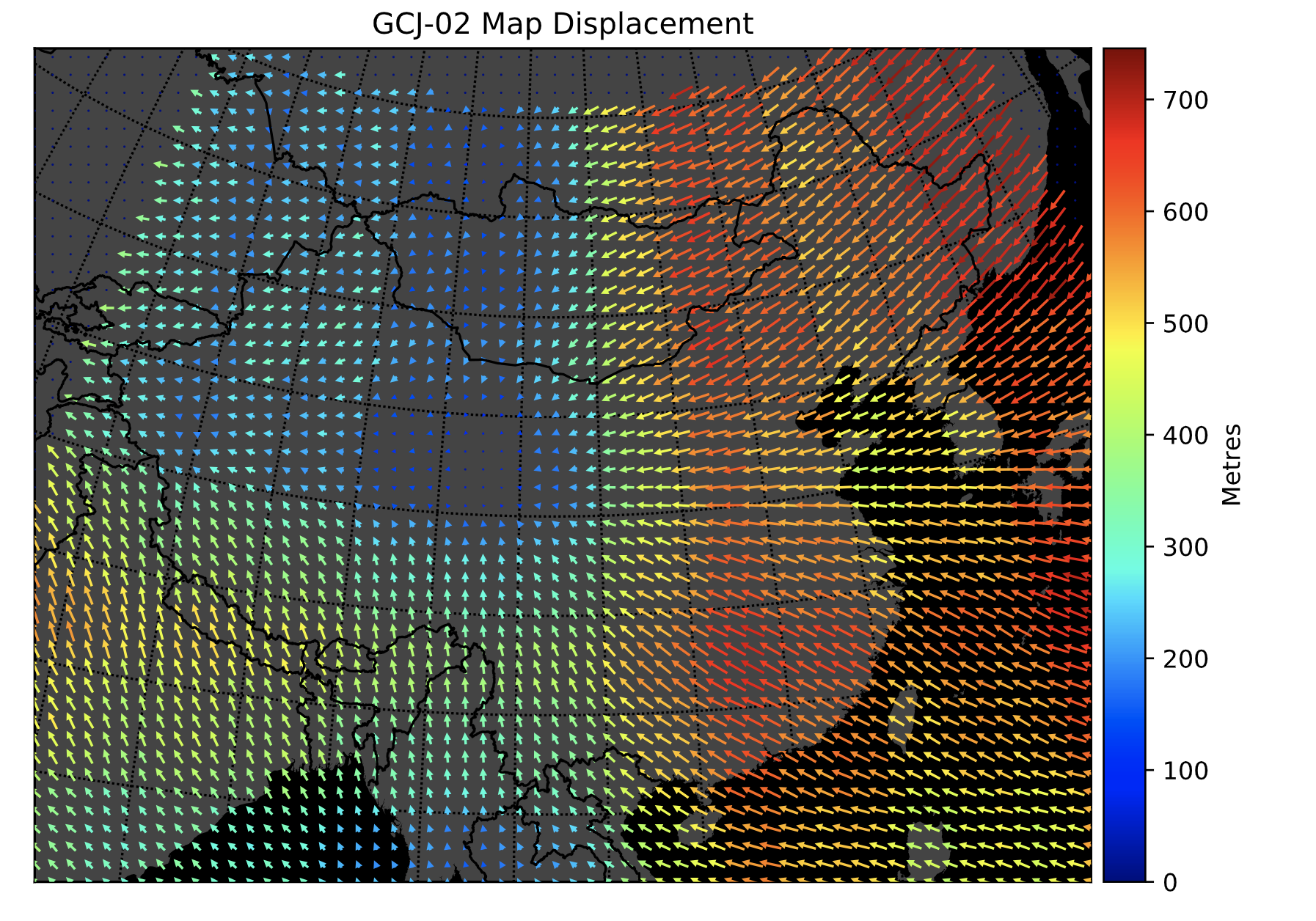

What I had gotten wrong about this was the consistency, or the guess that the offset was the same distance and direction everywhere, with some curvature-of-the-earth variations. But the actual implementation is of a decentralized offset, baked into a custom datum designated GCJ-02. All mapping data providers and application developers active in China must use this datum - or its relatives - as the basis of their maps, and it is technically against the law to provide transforms to more open standards like WGS84.

The notes from this 2011 party bulletin about the development of GCJ-02 are a fascinating study of the cultural and political considerations that always surround cartographers working in their field:

‘[Geographer] Li Chengming was confident: “In the war years, Communist Party members were not afraid of death, so what is this little difficulty! We must do it! And we must do it beautifully!” Under the guidance of veteran experts, he led his team to work for more than a thousand days and nights to develop a set of nonlinear confidentiality processing technology for topographic maps suitable for national series scales. This technology not only meets the national security confidentiality requirements, but also meets the public’s application needs for topographic maps.’

GCJ-02 and its like are not impenetrable. There are leaked documents and efforts at reverse-engineering that make it possible to achieve data interoperability. Perhaps even more interesting is this rendered transform from Leif Gehrmann - essentially a map of how maps are mapped in China:

I look at this and have to add “impressed” to my “appalled and mesmerized” feelings mentioned above. Obfuscation by datum is not something I would have really considered possible before, and it really is effective at reeling open standards into the net of state control. Cartography has a long and colorful history of serving Truth on the surface and Politics at its heart, and GCJ-02 is another entry alongside silver atlases, trap streets, and imagery blurring.