Steve Shell and his collaborators have an excellent anthology of gothic horror stories, told in podcast form: Old Gods of Appalachia1. It begins like this:

Long before our kind ever set foot in these mountains, when the peaks of the Blue Ridge towered above the stars, and the heart of the plateau still rolled with ridges tough as pine knobs, darkness was brought here in cages made of fear . . . These are some of the oldest mountains in the world. How dare we think we could break the skin of a god and try to dig out its heart without bringing forth blood and darkness?

Now, I’m not typically one for horror as a genre, but I’m a sucker for a well-told story, in sharp language, particularly if it’s been dropped into the slipstream of verifiable history. And the stories that Shell & co go on to tell are familiar to historians and bards both: tales of mine disasters, strikes broken in company towns, of witches and wards and wolves.

Chilling stories from bleak mountains

While the complete tapestry of the Appalachian experience is big and complex2, the dark tales fit with a repeated admonition in the folklore of the holler, that minding your own business is the key to safety3:

If you are out in the wilderness and you see something strange, no you didn’t. If you hear something call your name, no you definitely didn’t.

From the start, the Old Gods of Appalachia stories are woven into the fabric of the mountains themselves, partly explained by a vague evil lurking in the bedrock. This will sound familiar to Tolkein fans4:

The dwarves delved too greedily and too deep. You know what they awoke in the darkness of Khazad-dûm: shadow and flame.

Tolkein was drawing on his own intimacy with Norse, Saxon, and Celtic lore - with the tales that suggest there can be more than optical darkness beneath our feet, and that the pre-human histories of those depths can cause all manner of peril for us on the surface. And the bent ridges of Appalachia and the craggy hills of the British Isles are both very old indeed; “ancient” is too new a word to describe them5.

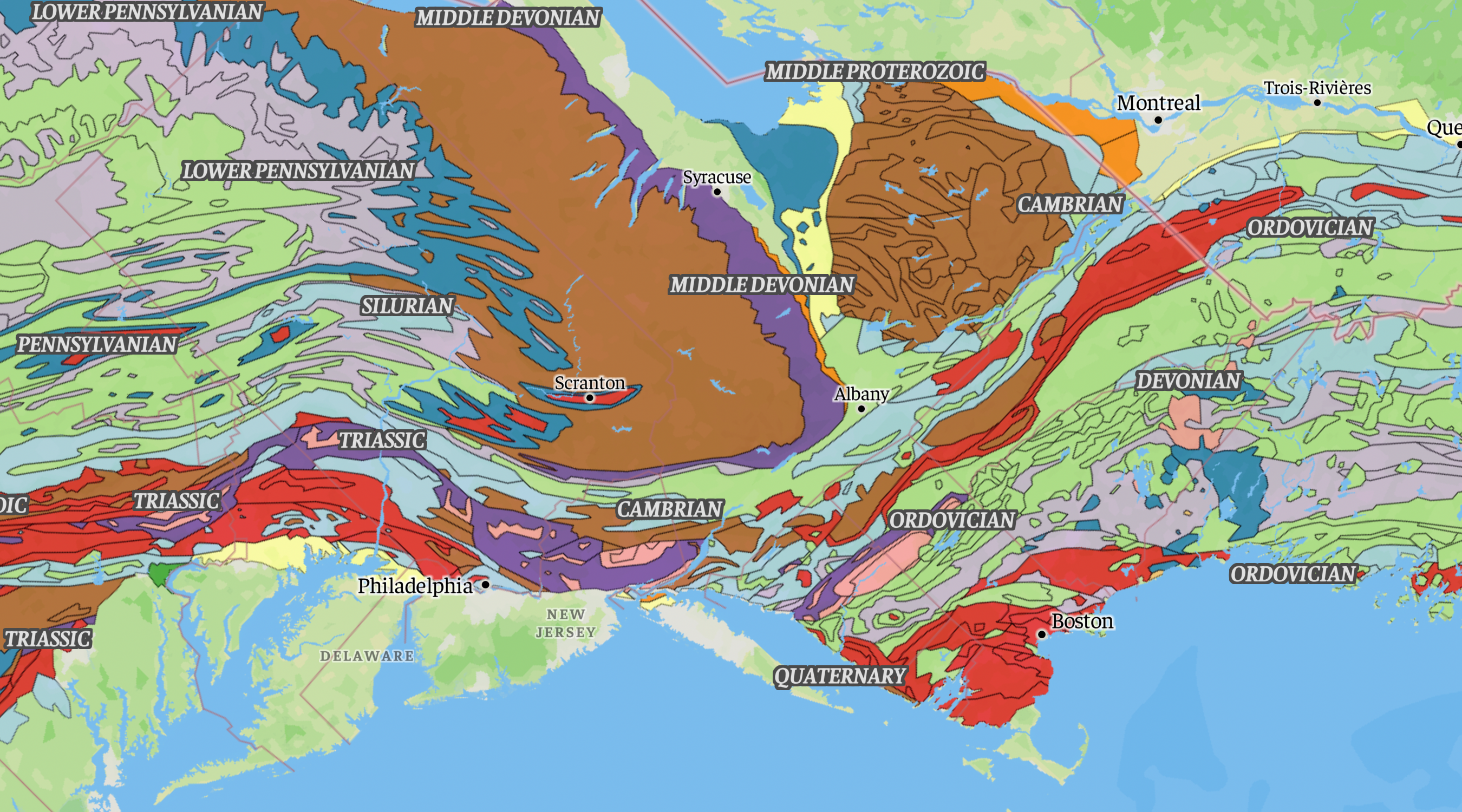

The geological subdivisions of greater Appalachia, grouped by maximum age (data source: USGS GMNA, map by me, full size download here)

The geological subdivisions of greater Appalachia, grouped by maximum age (data source: USGS GMNA, map by me, full size download here)

I have a different perspective than Shell and Tolkein. I’ve lived most of my life among the mountains of Northern Appalachia - “Apple-ayshia”, or what the Canadians call the “Uplands”. This is the Western part of a once-joined shield; when it split it waved goodbye to what are now Ireland and Scotland, its siblings6. This stretch of mountains is partly new. I grew up among the fresh granite batholiths that form the White Mountains in New Hampshire and the Kingdom Plateau in Vermont, relative newcomers that are still old enough to have since been split by the upstart Connecticut river. But these mountains are a riot of histories. Dozens of orogenies have formed them, and the oldest parts are old like the Earth itself. More than a billion years have passed since some of the stone in my neighborhood was first pushed above the surface.

Cambrian bedrock thrust above Ordovician shale in Burlington, Vermont, overgrown by tenacious conifers and flooded by the remnants of the Champlain Sea.

Cambrian bedrock thrust above Ordovician shale in Burlington, Vermont, overgrown by tenacious conifers and flooded by the remnants of the Champlain Sea.

Our stories here are different than the ones told by our Southern cousins. The Wabanaki and Mi’kmaq tell of Gluscabi the trickster7, an earthly, meddling god, who is himself very young - whose wise old grandmother keeps trying to set him straight. James Fenimore Cooper gave us heroics and travails and epic journeys8. Joe Citro has tried his damnedest to build horrible legends here9, but when he succeeds it’s with the raw material of modern lore. Robert Frost10 and David Budbill11 gifted us reflective, playful nature-poems, and Howard Frank Mosher12 wrote about community and redemption in the cross-border culture of these hills.

Of course there’s drama, but the darkness is all but absent. To the extent that it’s here, it’s because we’ve brought it on our backs from wherever we wandered. The mountains up here are silent observers, with no stake in our games. But this is the same rock spine that wends its way down to West Virginia and beyond. Ten miles from my house is a storied long-distance hiking trail13 that could take me all the way to “No, you didn’t” territory if I followed it. What’s at the heart of the difference?

Whence the darkness?

I’m reminded of something a teacher suggested to me many years ago: that the fairy tales collected and compiled by the Brothers Grimm - the “Kinder-und Hausmärchen”14, laden with violence, gore, cannibalism, and dark forces - were a product of things that the tale-tellers had themselves seen, and perhaps been party to. These fairy tales originated in the period of Central European history defined by the Thirty Years’ War15, the most horrific multigenerational conflict imaginable, full of crimes both documented and hinted at; humans unleashing their own darkness on each other. Daniel Kehlmann takes these stories a step further in his book “Tyll”16, placing the reader in the position of a lore-born figure from that time - a trickster demigod who witnesses the worst we can do, rather than causes it.

I lean toward Kehlmann’s perspective, and that of my teacher: that our stories reflect the darkness we visit on ourselves, and the hollows we inhabit are just the stages. This is also Carl Sagan’s view17:

The gods watch over us and guide our destinies, many human cultures teach; other entities, more malevolent, are responsible for the existence of evil. Both classes of beings, whether considered natural or supernatural, real or imaginary, serve human needs.

I sit in old mountains as I write this, but they don’t feel sinister; they’re solemn. They’re often described as gentle, and lush with green18. I think it’s no accidental contribution to that vibe that the last cannon was fired in anger here over two hundred years ago, though Vermonters have intimately known the wars of other places in that time19. Dark ages result in dark tales, and sometimes the converse is true.

I have great respect for the folk of Southern Appalachia, and in many ways their lot has been much harder than ours up here; our extractive period is largely undone20, while the legacy of theirs will linger for centuries21. But I think their talent for tying good yarns to the old earth might mask a hard truth: that we are the cause of our own sorrows. To say so doesn’t diminish them, but lets us look them straight in the eye.

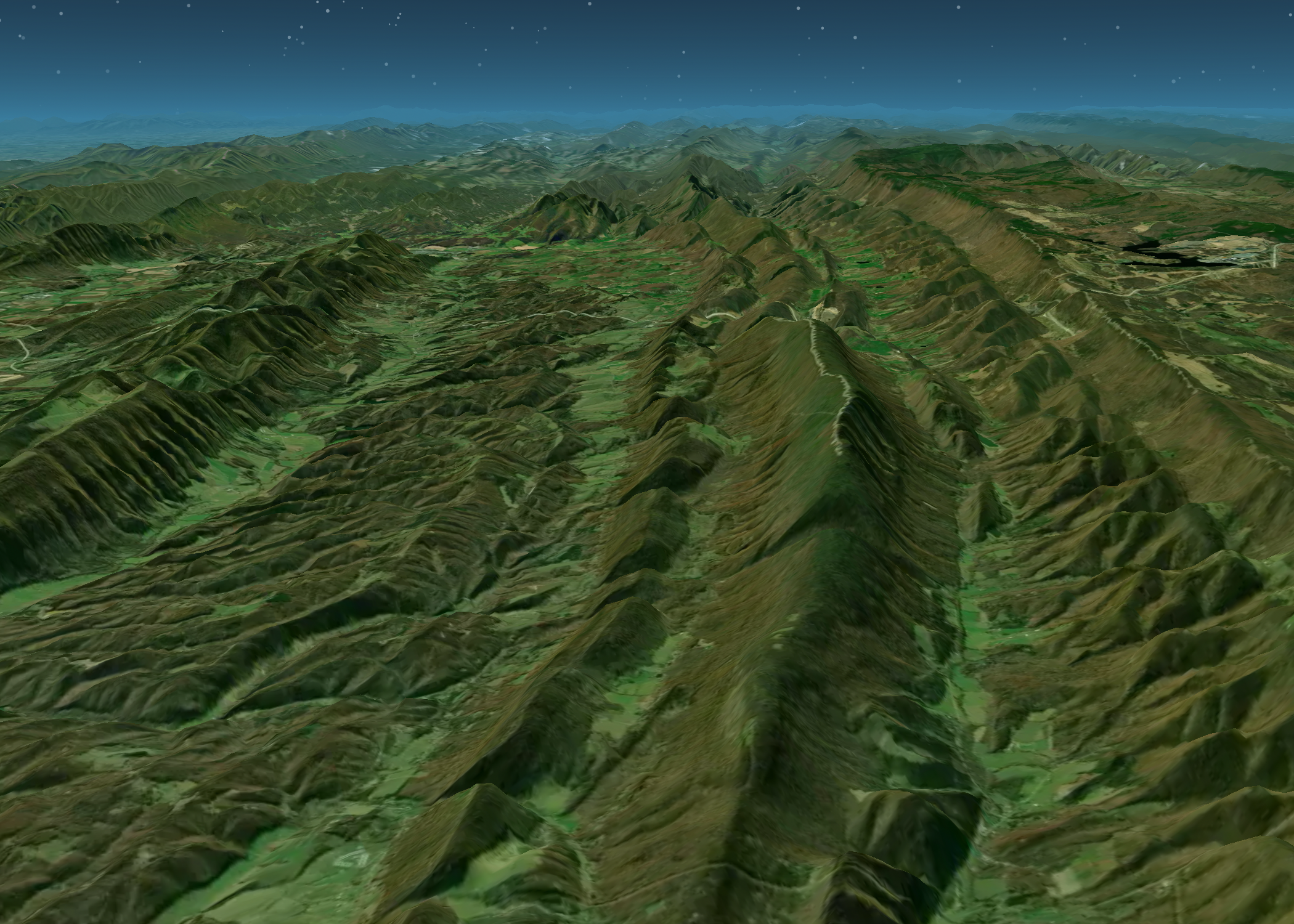

The ridges, valleys, and hollers of Grant County, West Virginia (map by me)

The ridges, valleys, and hollers of Grant County, West Virginia (map by me)

Notes and reading list

Thanks for enduring my first experiment with markdown footnotes. I’m pleased that it resulted in a standalone bibliography, and I encourage you to run down the great stories listed below.

-

Old Gods of Appalachia, start at the beginning with the prologue ↩

-

Barbara Kingsolver has an excellent tour this week in the NYT Book Review of what it would be an insult to call “regional literature”, but for which I don’t have a better term. ↩

-

This advice seems to make the rounds regularly on TikTok and YouTube, so take that with a big ol’ grain of salt. ↩

-

Tolkien J. R. R. 1994/1966. The Fellowship of the Ring. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ↩

-

If you like tangible metaphors - like zippers and elevator doors - in your geologic history of the Appalachian highlands/uplands, Chris Tacker of North Carolina State has got the post for you. ↩

-

It’s not tremendous hyperbole to say that Marie Tharp & co. were set on the path to identifying plate tectonics because Canadian and British geologists kept sensing eerie similarities between their landscapes. ↩

-

Dana Carol A Margo Lukens and Conor M Quinn. 2021. Still They Remember Me. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ↩

-

Cooper James Fenimore. 1896. The Last of the Mohicans : A Narrative of 1757. New York: T.Y. Crowell. ↩

-

Citro Joseph A. 2000. The Gore : A Novel. Hanover NH: University Press of New England. ↩

-

Frost Robert. 1977. North of Boston : Poems. New York: Dodd Mead. ↩

-

Budbill David. 1991. Judevine : The Complete Poems 1970-1990. Post Mills Vt: Chelsea Green Pub. ↩

-

Mosher Howard Frank. 1985/1978. Where the Rivers Flow North. New York N.Y: Penguin Books. ↩

-

Shouts to my friend Brendan, currently Southbound on the Appalachian Trail and somewhere in the spooky Alleghenies as of this writing. ↩

-

Grimm Wilhelm Jacob Grimm and Oliver Loo. 2014. The Original 1812 Grimm Fairy Tales : A New Translation of the 1812 First Edition Kinder- Und Hausmärchen Children’s and Household Tales. Pennsylvania: publisher not identified. ↩

-

The brutality of the Thirty Years’ War really cannot be overstated. Millions died in Germany alone, in a time when that was a big proportion of the total population. ↩

-

Kehlmann Daniel and Ross Benjamin. 2020. Tyll. First American ed. New York: Pantheon Books. ↩

-

page 115: Sagan Carl. 1997. The Demon-Haunted World. New York: Ballantine Books. ↩

-

Albers Jan. 2002. Hands on the Land : A History of the Vermont Landscape. Cambridge Mass: MIT. ↩

-

Wilder Frankie. 1862. The Death of Henry Harrison Wilder. Burlington: University of Vermont. https://cdi.uvm.edu/manuscript/uvmcdi-95736. ↩

-

Vermont in particular was famously 80% deforested a century ago; now it is close to 80% afforested. The secret? Economic inversion and flat population growth. ↩

-

The scars are visible from space, and will be for a long time to come. ↩