Xinjiang, China

There is a road in the Taklamakan desert that doesn’t bother to snake its way around dry streambeds or rocky landforms, it plows mostly straight through the dunes. The G580 runs between the cities of Hotan and Aral, and on close inspection, it’s clear that there’s a buffer of some kind to a distance on either side of the pavement.

Credit where it’s due: the linked photos via Google Maps were the only way to really see what this is: A gridded shield of grasses, carefully planted and maintained, to stave off the drifting sand. Special thanks to Guilkoo Choi for offering the ground-level view:

I cannot even begin to imagine how much it costs to keep this road open.

Pyongyang, North Korea

The hermit kingdom is trolling me. Or more accurately, they’re trolling the many foreigners whose only window into North Korean life is from satellite imagery. The national Sci-Tech Complex in the capital city is - yes - built in the shape of an atom, suggesting that Kim Jong-un’s nuclear-obsessed regime is aware of and poking at the rest of the world’s equal obsession with North Korean nuclear capabilities.

According to state photos and press releases, the not-unattractive structure is basically a big, ruthlessly-curated library. Books on the shelves are notably in English and French. And of course there’s a big-ol’ ICBM in the very center of the atom’s nucleus, but let he who has never used a missle as a public art installation cast the first stone.

Kisangani, DR Congo

A satellite in polar orbit swings fast around the Earth, one full circle every 100 minutes, as the planet spins beneath. An instrument mounted on such a satellite can capture an image of the same spot on Earth roughly once every 1-3 days. With the right uplinks and data processing, a single point on land could have hundreds of “looks” per year from one satellite. But then there are clouds.

Some regions are notorious among the remote sensing community for offering satellites nothing but white fluffiness in all those overpasses: mountainous regions in China and Ecuador, the Amazon rainforest, and The Congo river basin. In this last one, 2,500 miles upriver from the ocean, is a decrepit train station. The rail lines are just visible through a rough haze, in the clearest look that Maxar’s WorldView-3 satellite was able to get in the course of Kisangani’s nine-month rainy season. This part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is simply shrouded from satellites most of the time.

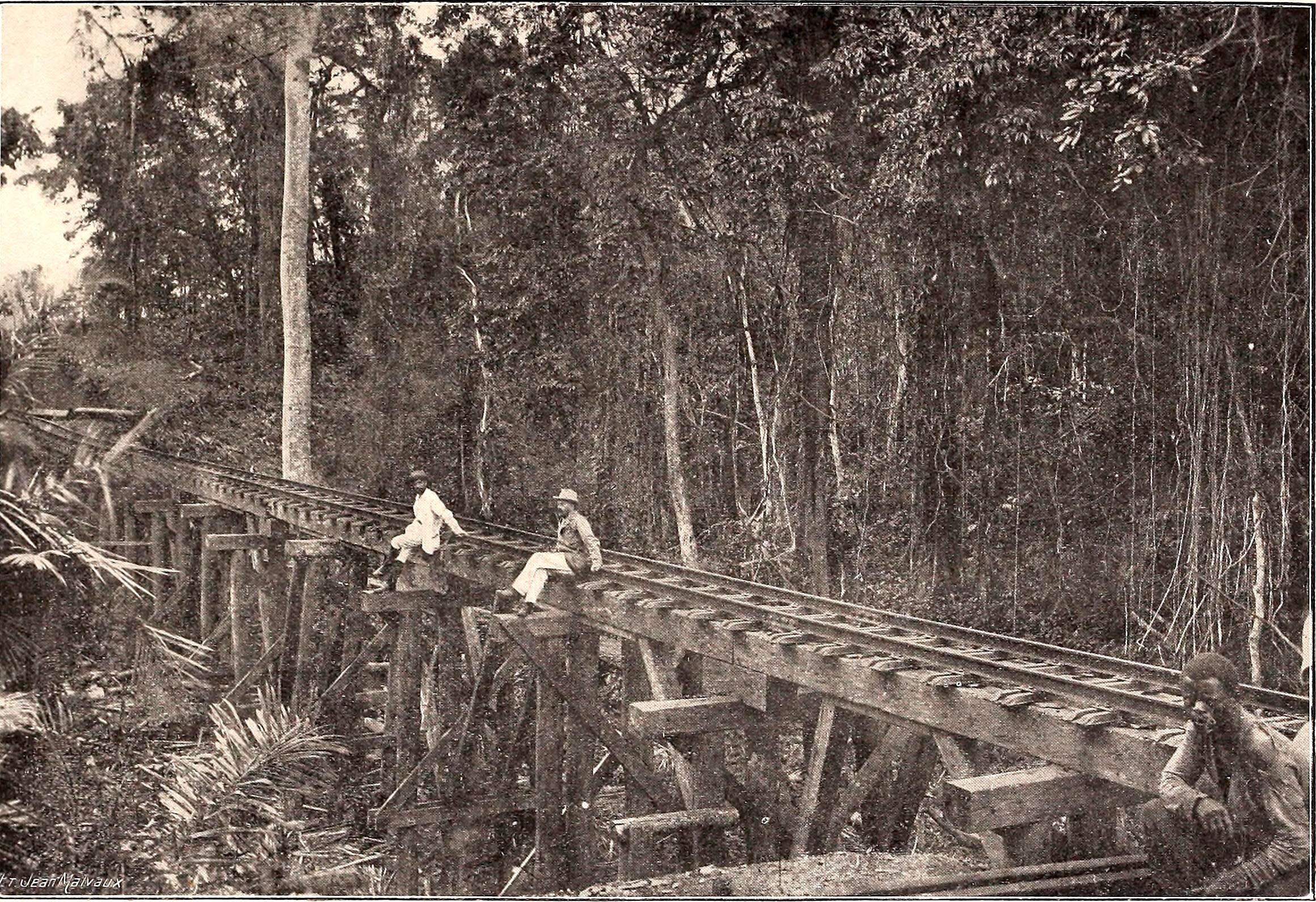

The train station we can glimpse here is positioned just below an impassable stretch of cataracts called Boyoma Falls, and it was constructed at the turn of the last century under the direction of Leopold II’s Congo Free State, to serve as the terminus of a portage rail line that bypassed the falls. Leopold’s nearly-vampiric motivations and methods for exploiting the Congo are well-documented elsewhere, but this train station has been in intermittent service ever since its construction, carrying both goods and passengers.

Trestle on the Stanleyville (now Kisangani) line, 1907 - Jean Maivaux

This rail line and others in the DRC have existed to facilitate extraction of resources. First rubber and timber, then copper, then cobalt, then lithium. These last are the lifeblood of the ascendent global tech industry, and the stated-and-unstated cause of wars that have roiled Eastern Congo for decades. Leopold may be gone, but great powers still fight and cajole over the region. Maintaining this line is expensive as the tropical environment constantly tries to reclaim it; passenger service alone fails to pay the costs. Last month a South Korean firm signed a $257 million deal to begin rehabilitation of the infrastructure. It will need an upgrade to carry the expected freight.

The rails themselves are just visible through the haze of the image. The viewer can follow them Southeast as they leave the yard, and curve through tight neighborhoods. The line is closed in by the forest South of Babusoko, on the way to Ubundu. The imagery here is a decade old, with subsequent cloud-free looks in short supply.