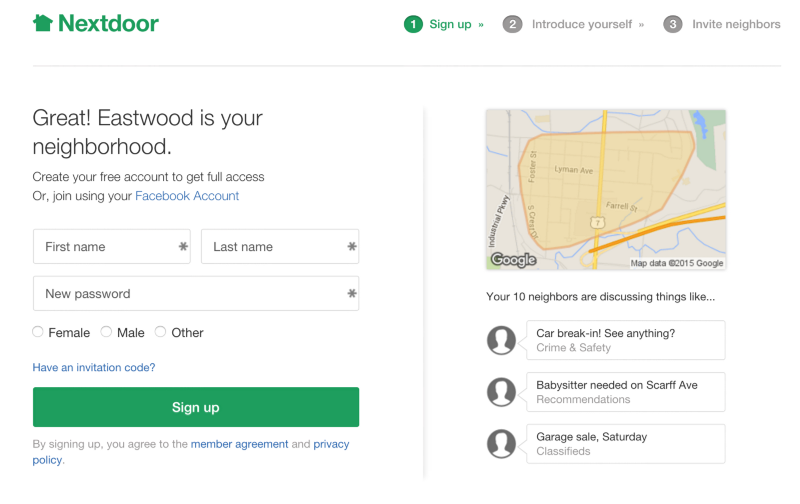

Upon the occasion of Halloween, and the need to optimize, I took a look at NextDoor for the first time. They apparently had some sort of dope candy-targeting map for every neighborhood, and since that’s my catnip I had to check it out. Step 1: sign up, because the candymap is actually just a big inbound marketing trap:

Where I live, according to NextDoor

Eastwood. Awesome. Never heard of it.

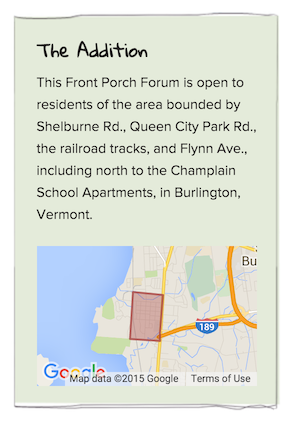

You see this is Burlington, Vermont — where a NextDoor precursor/competitor called Front Porch Forum has been merrily providing me with neighborhood gossip and news for a damn long time. And in that world I’m part of the (accurately-delineated) neighborhood known as “The Addition”:

Where I live, according to Front Porch Forum

Leaving aside questions of geographic or customary accuracy (I’ve already spilled too much ink there), I realized that these were two parallel streams of information. Maybe the reports of missing cats, rants about parking and occasional racist dogwhistles (seriously Trent, stop it.) overlapped between FPF and NextDoor, but maybe a lot was being lost. What if someone on the next block has been posting to NextDoor for months, looking for the adorable wallaby that snacks on my azaleas every morning? The thought of such vital information missing its target because of platform lock-in is almost too much to bear.

Vital information misses its target all the time because of platform lock-in.

Last year at a statewide digital conference <insert joke about Vermont and smoke signals>, I met a woman who — like me — had gotten her start in online organizing during hurricane Irene.

Irene says hi. Photo by Stephen Flanders

Irene says hi. Photo by Stephen Flanders

Quick background: at the end of the summer in 2011, a random hurricane veered off course and wandered up the Green Mountains, cutting off whole towns, killing electricity statewide and incidentally flooding the VT office of emergency management out of their building. In the days and weeks afterward, some colleagues and I used Ushahidi and straight-up Wordpress to fill the gap in the information plumbing, relaying help requests and offers between victims, responders and the public, over any channel we could plug into.

But this woman hadn’t heard of our efforts (the nerve!) even though information about her hard-hit town had definitely passed through our pages. Instead, she had exclusively used a Facebook page to rally donations, supplies and volunteers. I mentally slammed my head against a brick wall a few times, recalling that Facebook — absent a public newsfeed API — was the one major social channel we hadn’t been able to tap. It was incredibly frustrating at the time knowing that aggregation wasn’t possible from that direction — knowing that responders were being forced to sift through dozens of Facebook pages in addition to the single-point firehose that we (and later Google Crisis Response) created.

And the greater concern — the bogeyman in this terrifying data-parable — was whether anyone fell through the cracks. Specifically, did anyone die or suffer in any way because Facebook was and remains a social silo?

I’m pretty sure the answer is no. Life and death hinging on the social web is still sort of an edge case. S ocial data, however, is definitely getting locked into a series of well-worn ruts, along with the rest of our media diets (see: The Filter Bubble). The effect of it seems like it should be scale-dependent, with the likelihood of negative impact inversely proportional to the scale:

- Missing a world news story about oil prices probably isn’t going to ruin your day.

- Missing a congressional corruption scandal won’t necessarily hurt your paycheck, but might have affected your next vote.

- Missing a town meeting announcement might mean you stumble into an unexpected roadwork delay on your commute.

- Missing a “Found a wallaby” post on your block could mean that Fluffy has a new owner and you never find out about it.

But there are lots of channels, with messages repeated over many of them. Adwords, Twitter, listservs, posters stapled on telephone poles.

Photo by Simon Cousins

Photo by Simon Cousins

As long as the channels are open the redundancy should do its work for the really important stuff (Twitter notifications to Slack, for instance), and at the neighborhood level the power of the analog still reigns.

“Fluffy! I’ve got some azaleas for you! Yum! HEEEERE FLUFFYYYYYYY”

What worries me is a future where — at whatever level we call our “community” — we become partitioned from each other. Where Twitter v. Facebook is as socially-segregating a choice as Liberal v. Conservative. Where the parallel universes of NextDoor and Front Porch Forum never interact in real life either, no matter how meaningful the subject.